A Primer on Cryptocurrency Investigation and Forensics

An introductory exploration of Cryptocurrency Investigation and Forensics, including challenges posed by money laundering techniques and the role of blockchain intelligence and taint analysis in unveiling concealed financial activities, with a demo on a real-world RaaS case.

A wise person should have money in their head, but not in their heart. ― Jonathan Swift

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Intricate Dance of Money Laundering

- Cryptocurrency Strategies to Conceal Illicit Funds

- Tracing Illicit Crypto Transactions

- Lost in the Shadows – Demo on a Real-World RaaS Attack

- Conclusions

Introduction

Picture this: a serene lakeside town, nestled in the heart of the Ozarks, where the placid surface belies the turbulent currents beneath. Just like the acclaimed TV series “Ozark”, where idyllic landscapes mask a world of intrigue and danger, the realm of money laundering presents a similar dichotomy. Welcome to the world where technology, finance, and crime intertwine in a dance that echoes the enigmatic rhythm of the Ozarks itself. In the hit series, Marty Byrde, a financial planner, finds himself embroiled in a web of criminality that compels him to orchestrate intricate money laundering schemes. While our journey might not involve drug cartels and tense showdowns, it does lead us through the complex tapestry of cryptocurrency, blockchain, and the modern art of disguising ill-gotten gains.

Likewise the characters in “Ozark” navigate a world of shifting alliances and hidden motives, in this article we will explore the virtual realm where criminals seek refuge while investigators strive to bring them to justice. So, let’s grab our metaphorical detective hat and embark on a journey into the fascinating world of Cryptocurrency Investigation and Forensics. In particular, this article includes the challenges posed by money laundering techniques and the role of blockchain intelligence and taint analysis in unveiling concealed financial activities, with a demo on a real-world RaaS case. Arguably, this article refers to Bitcoin as a notable cryptocurrency sample, yet most of the concepts remain valid for other cryptocurrencies.

The Intricate Dance of Money Laundering

Money laundering, an age-old financial crime, has evolved into a complex web of illicit activities that span both traditional financial systems and the digital realm. In the digital age, where cryptocurrencies and innovative technologies reign, criminals are finding new ways to conceal their ill-gotten gains. To counter this escalating threat, anti-money laundering (AML) has gained prominence in both the financial and legal sectors as a means to prevent, detect, and report money laundering activities. Such a focus on AML has been catalysed by the establishment of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and the subsequent development of international standards. These gained greater significance in the early 2000s when FATF began publicly identifying countries with deficiencies in their AML laws and international cooperation, a practice colloquially referred to as “name and shame”.

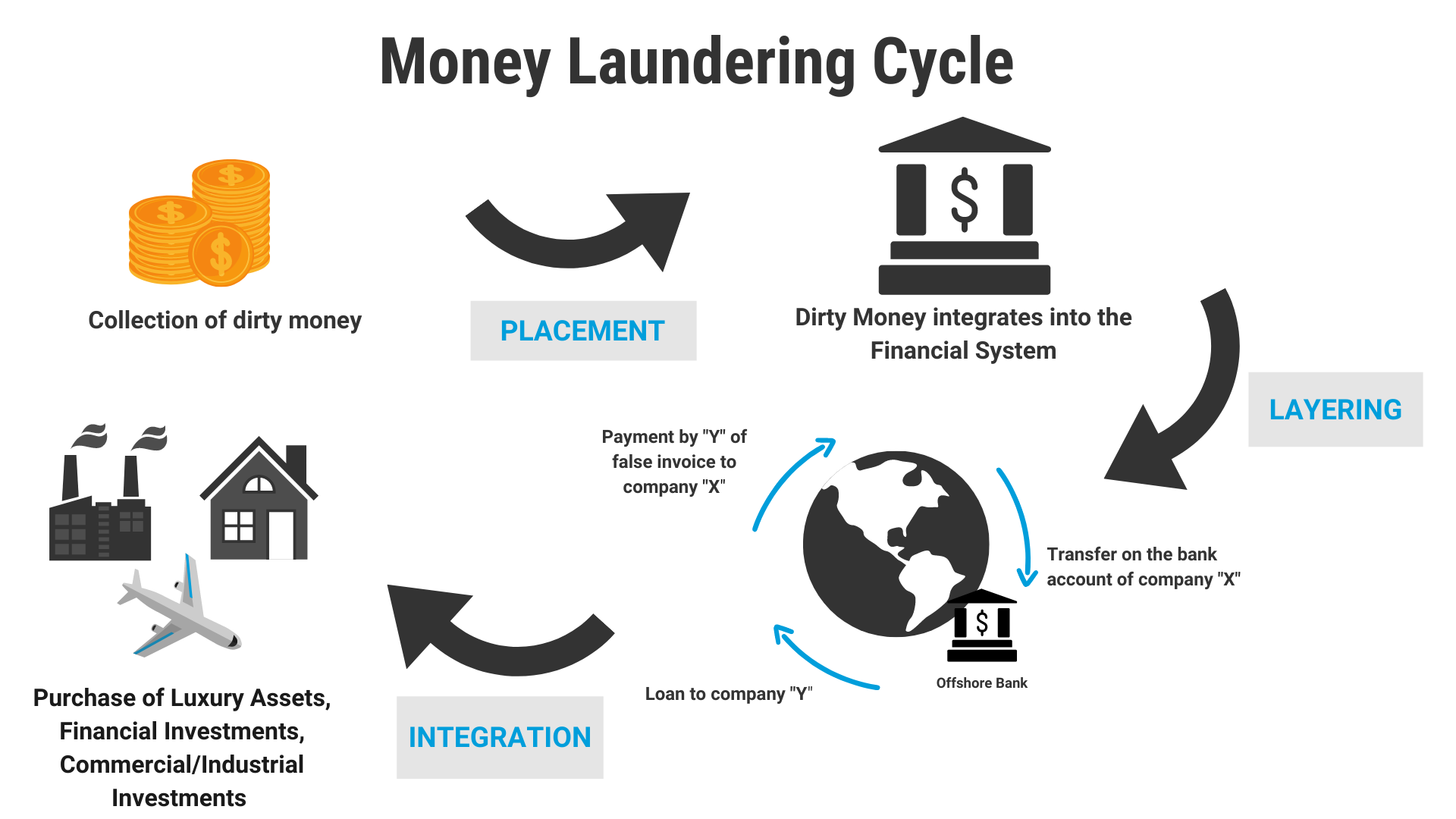

Money Laundering Model

Money laundering is not a simple act of washing cash; it’s an intricate dance orchestrated by criminals to legitimise the proceeds of their illegal endeavours. At its core, money laundering transforms “dirty” money into a legitimate source, making it difficult for law enforcement to trace back to its criminal origins. The process involves three key stages: placement, layering, and integration.

- Placement: criminals inject their illicit funds into the legitimate financial system. This can involve funnelling cash through seemingly legitimate businesses or making small deposits to avoid suspicion.

- Layering: it is a process designed to obscure the source of funds. This is achieved by executing a series of transactions and using various bookkeeping tricks to create confusion and complexity.

- Integration: the “cleaned” money is reintroduced into the economy and used for lawful purposes, making it nearly impossible to distinguish it from legitimate funds.

Several Flavours of Money Laundering

There are multiple, different forms of money laundering, yet they can be categorised under one of the following types: bank methods, smurfing, currency exchanges, and double-invoicing. In particular, smurfing (also known as “structuring”) involves criminals breaking up large chunks of cash into multiple small deposits, often spreading them over many different accounts, to avoid detection. Furthermore, money laundering can also be accomplished through the use of currency exchanges, wire transfers, and “mules”-cash smugglers, who sneak large amounts of cash across borders and deposit them in foreign accounts, where money-laundering enforcement is less strict.

Other common money-laundering methods – a complete list is available here – include:

- Bulk cash smuggling to another jurisdiction and (physically) depositing it in a financial institution, such as an offshore bank;

- Investing in commodities such as gems and gold that can be moved easily to other jurisdictions;

- Discreetly investing in and selling valuable assets such as real estate, cars, and boats;

- Cash-intensive businesses where activities (e.g., parking structures, strip clubs, tanning salons, car washes, arcades, bars, restaurants, etc.) use their accounts to deposit criminally derived cash;

- Round-tripping where money is deposited in a controlled foreign corporation offshore, preferably in a tax haven;

- Gambling and laundering money at casinos;

- Counterfeiting; and

- Using shell companies (inactive companies or corporations that essentially exist on paper only).

Cryptocurrency Strategies to Conceal Illicit Funds

Cryptocurrencies offer a distinctive advantage over traditional fiat currencies like the U.S. dollar – the veil of pseudonymity they provide. While blockchain technology ensures that all transactions are transparent, immutable, and accessible to everyone, the identities of the individuals behind these transactions remain concealed behind a string of alphanumeric codes, namely a crypto wallet public key. The pseudonymous nature of cryptocurrency transactions creates a conundrum for those tasked with forensic investigations. Hence, government agencies, cybersecurity firms, and individuals striving to unearth the senders and recipients of crypto assets linked to nefarious activities face a formidable challenge. To this extent, the FATF considers many businesses that offer cryptocurrency services to be virtual asset service providers (VASPs) - VASPs fall under Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) money laundering rules, obligating them to implement AML processes, as traditional financial organisations. Moreover, being stored transparently on public blockchains, crypto transactions also present cybercriminals with a unique set of challenges that, if properly faced, may turn into opportunities, as the ecosystem of marketplaces and exchanges facilitate each of the money laundering stages discussed above. These stages can then be viewed from the perspective of cryptocurrency-enabled money laundering:

- Placement: launderers can place fiat money by exchanging it for crypto on cryptocurrency exchanges. They can place cryptocurrencies by moving them from wallets associated with unlawful activity to exchange wallets. They can also exchange mainstream cryptocurrencies with traceable transaction histories for “privacy coins” engineered to obscure transaction histories and make it impossible to establish an audit trail.

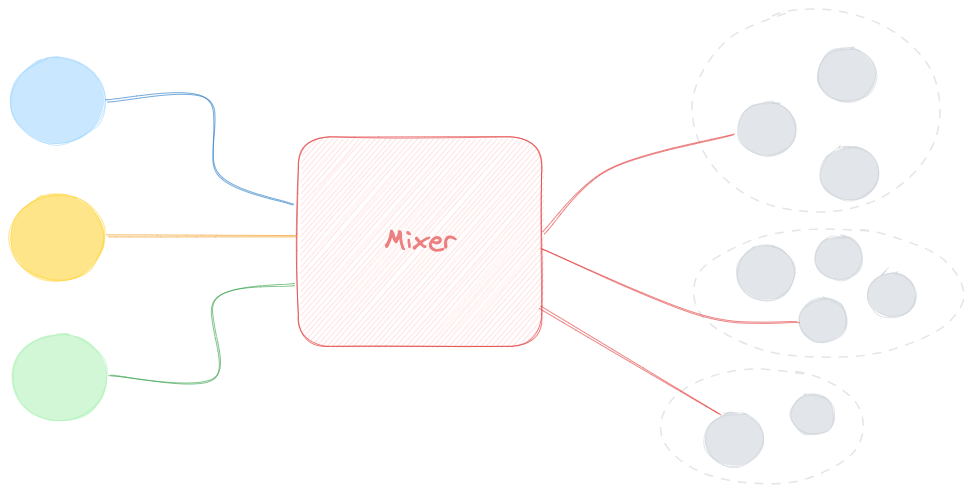

- Layering: here cryptocurrencies are particularly useful to criminals. The simplest technique is creating many different cryptocurrency wallets and sending crypto from one to the other, often in small chunks, obscuring the crypto’s origins in potentially thousands of transactions. Additionally, launderers can use blender, tumbler, and mixer services, as we shall detail below. These pool cryptocurrencies from multiple sources and carry out thousands of random transactions via wallets and fake exchanges. Eventually, the crypto is returned to the original owner in random increments at randomly determined times, making it extremely difficult to establish its origin.

- Integration: once its origins are obscured, the cryptocurrency can be reintroduced into the financial system. This might be as simple as exchanging it for fiat on a cryptocurrency exchange or via a cryptocurrency ATM.

In addition to traditional cryptocurrencies, Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) have also become intertwined with money laundering activities. NFTs frequently serve as instruments for Wash Trading, a practice involving the creation of multiple wallets for a single individual, generating fictitious sales, and subsequently selling the corresponding NFT to a third party. In brief, an individual buys an NFT they already own using different private keys. A launderer buys a low-priced NFT using one set of cryptographic keys. They (or a trusted third party) then rebuy it using criminal proceeds with different keys, thus creating a sale record and demonstrating a legitimate source for their money. Finally, they sell the NFT to an unsuspecting buyer – if the launderer is careful, connecting both sets of keys to the same individual is almost impossible. According to Chainalysis, wash trades using NFTs are gaining popularity among money launderers due to the relatively anonymous nature of transactions on NFT marketplaces. Thus, regulatory pressures are mounting on auction platforms facilitating NFT sales to comply with anti-money laundering legislation. The Department of the Treasury’s Study of the Facilitation of Money Laundering and Terror Finance Through the Trade of Works of Art has warned that NFTs used for investment may meet the FATF’s definition of virtual assets and, as a result, companies facilitating NFT trading may be considered VASPs.

Moreover, online gaming has also emerged as an increasingly common avenue for money laundering. Various online games, including Second Life and World of Warcraft, enable the conversion of money into virtual goods, services, or virtual cash that can subsequently be converted back into real currency.

Within the above introduction, we may now provide the most common methods – we may also refer to these as instances of Anti-Forensics – that involve the use of cryptocurrencies leveraged by criminals to conceal dirty money.

Crypto Mixers

Crypto mixers, also known as tumblers or blenders, serve as a smokescreen for cryptocurrency transactions. These services allow users to deposit their assets into a communal pool, where the funds become intermingled with those of others. The user then withdraws a different combination of coins from what they initially deposited, making it exceptionally challenging to trace the original source. The process involves a complex series of transfers, effectively obscuring the flow of funds. This strategy capitalises on the anonymity of the shared pool, making it nearly impossible to deduce which participant’s funds correspond to which transaction. As a result, investigators face a daunting puzzle of intertwined transactions, with obscured pathways leading to a multitude of wallet addresses. While the legality of mixers is contentious, they are not explicitly illegal in many jurisdictions. In fact, advocates contend that mixers protect user privacy, and they assert that governments lack the authority to restrict access to decentralised software. In the United States, FinCEN mandates mixers to register as money service businesses.

Layering Transactions

Layering transactions involve sending numerous transactions through multiple intermediary wallet addresses. These transactions eventually consolidate into a single transfer. This entanglement of addresses can delay the identification process, granting criminals time to offload funds before their addresses become blacklisted, as it serves to blur the connection between the source and the destination. In fact, layering transactions presents law enforcement with an arduous task, as the sheer volume of transactions to unravel can create a time-consuming obstacle. Nested services can potentially be used as part of layering transactions. These services, operating within one or more cryptocurrency exchanges, use addresses hosted by exchanges to access exchange liquidity and take advantage of trading opportunities. Some exchanges have lax compliance requirements for nested services, making them susceptible to exploitation for money laundering. On the blockchain ledger, transactions involving nested services often appear as if they were conducted by the exchange itself rather than the nested service or individual addresses. Over-the-Counter (OTC) Brokers are a prevalent and notorious type of nested service. They enable traders to securely and anonymously trade significant amounts of cryptocurrency and facilitate direct cryptocurrency transactions between two parties, without the need for an exchange intermediary. These trades can be made between different cryptocurrencies (e.g., Ethereum and Bitcoin) or between cryptocurrencies and fiat currencies (e.g., cryptocurrencies, like Bitcoin and fiat currencies, like euro). In addition, OTC brokers connect parties for a transaction and charge a commission but do not participate in the negotiations. Once terms are agreed upon, custody of the assets is transferred through the broker.

Peer-to-Peer Transactions

Criminals often cash out stolen crypto by selling the assets for cash through peer-to-peer arrangements. This bypasses the rigorous know-your-customer (KYC) and anti-money laundering checks of centralised exchanges, enabling them to transfer tainted funds to unsuspecting individuals. Thanks to peer-to-peer transactions, criminals opt for direct sales to individuals, bypassing the stringent regulations and oversight prevalent in centralised exchanges. This strategy typically involves individuals unwittingly receiving illicit funds, as they believe they are engaging in legitimate transactions. The inherent pseudonymous nature of cryptocurrencies aids in maintaining anonymity throughout these peer-to-peer dealings, making it challenging for investigators to trace the origins of these funds.

Peel Chain

The concept of peel chain adds yet another layer of complexity to the world of cryptocurrency laundering. In this technique, a criminal initiates a sequence of transactions, with each transfer peeling away a fraction of the funds. This gradual process fragments the original sum into smaller portions, reducing the likelihood of detection during subsequent transfers. The rationale behind the peel chain is twofold: it disguises the true value being transferred and mitigates suspicions triggered by large, sudden transfers. By gradually moving funds through multiple addresses, cybercriminals create a scenario where each transaction seems less noteworthy, making it harder for investigators to identify the overarching purpose.

Tracing Illicit Crypto Transactions

Complementing the study of investigating criminal activities on the blockchain (aka Blockchain Forensics), the intelligence operations behind Crypto Investigation and Forensics unveil the broader landscape of cryptocurrency transactions. This field delves into the realm of patterns, behaviours, and trends exhibited by digital assets as they traverse the blockchain. Furthermore, it requires a comprehensive approach that combines blockchain forensics with off-chain investigation, e.g., analysis of the scheme’s timeline, use of forensic analysis to identify account owners and related addresses, legal avenues such as subpoenas and warrants necessary to identify scheme operators fully. Additionally, due diligence may include background checks on scheme principals, examining criminal history, financial records, and past involvement in fraud. For international cases, coordination with overseas sources may be required. The most common areas of analysis and fact-finding are:

- Attribution Data: blockchain intelligence tools gather and analyse ownership attribution information, which helps de-anonymise blockchain addresses. This information can identify associations with criminal groups, fraudulent schemes, and transactions with relevant entities like exchanges and fiat off-ramps used to convert criminal proceeds.

- Transaction Mapping: transactional data is visually represented in maps and flowcharts, revealing interactions with exchanges and other entities. This mapping aids in recognising patterns commonly used for money laundering, such as layering and peel chains. Expert investigators employ automated tools for efficient evidence collection.

- Cluster Analysis: clusters represent groups of cryptocurrency addresses controlled by the same entity. Expanding investigations from one address to a larger cluster provides more evidence for de-anonymisation and asset tracing. It can also determine if linked addresses hold substantial value.

- Subpoena Targets: cryptocurrency exchanges, DeFi (Decentralised Finance) firms, and virtual asset service providers complying with KYC and AML regulations require customer identity verification. This information can be valuable for de-anonymising individuals who have used these services. Personally identifying data may be obtainable through subpoenas.

- Current/Historical Value: addresses with significant cryptocurrency holdings are crucial indicators for financial recovery, potentially leading to seizure warrants or garnishments.

- Total Transactions: transaction volume can indicate the scale of a fraud scheme and the number of victims, influencing law enforcement attention and potential civil suits.

- Risk Profiling: automated risk-scoring algorithms trace target address activity and identify associations with known entities, including exchanges, mixers, and sanctioned parties.

- IP Address: blockchain surveillance systems collect metadata, including IP addresses associated with transactions, providing geographical location information.

In the pursuit of tracking down the owners of specific crypto wallet addresses, two forensic techniques have emerged, including the identification of common spending patterns and the analysis of address reuse.

The identification of common spending patterns serves as a powerful technique in the arsenal of blockchain investigators. By analysing multiple-input transactions, where different crypto wallet addresses contribute to a single transaction output, investigators can infer connections between these addresses. This approach hinges on the premise that individuals are unlikely to share private keys or passwords, signifying that multiple addresses with shared inputs likely belong to the same user. Furthermore, there are also cases where the user may be using different output wallet addresses to try and hide the money flow. Here, the detection of the change output can help to track a single user’s activity across a series of transactions. The intricate dance of transactions between these addresses paints a picture of how cybercriminals disperse funds. The ability to distinguish these patterns offers valuable insights into the structure of criminal networks and the flow of ill-gotten gains. To streamline this process, cutting-edge technologies leverage clustering algorithms that automatically identify common spending patterns, enabling investigators to focus their efforts on untangling the threads that link these addresses.

Another strategy that comes into play is address reuse analysis. In the labyrinth of cryptocurrency transactions, some wallet addresses emerge as repeat players in the sequence of transfers. This phenomenon often points to a significant element – an address repeatedly used as the output for various transactions. By identifying these reused addresses, investigators gain a foothold in their pursuit of the perpetrator’s wallet address. This technique relies on the assumption that a reused address represents a control point on the web of transactions. It allows investigators to focus their attention on this pivotal address, tracing the intricate paths of incoming and outgoing transactions. These reference points help filter out extraneous addresses tied to services, exchanges, or other intermediaries, sharpening the investigative focus.

The concepts that we have discussed so far should be taken into account when employing blockchain analysis heuristics and tools, as we shall detail below.

(Block)Chain Analysis

Chain analysis adopts heuristics to analyse the blockchain and trace the ownership of cryptocurrency across transactions. The most common form of chain analysis is taint analysis, which is focused on the identification of transaction “change” outputs. This process is a way of tracing crypto transactions to see where they came from and where they have been, with the ultimate aim to follow a user’s activity over multiple transactions. If such an on-chain activity leads to an identified economic entity’s wallet cluster, investigators may be able to obtain user PII (Personal Identifiable Information) associated with the observed transaction activity. Taint analysis can be useful in tracing when someone is trying to launder money or hide the source of their funds. In general, there are three main heuristics employed for chain analysis:

- Largest Output Amount – the output with the largest amount of funds is likely to be the change address;

- Round Number Payment – the output with a round number amount of funds is likely to be the payment.;

- Script Type – the output with the same script (address) type (e.g., P2SH, P2PKH, etc.) as the input is likely to be the change address.

The arena of blockchain analytics tools emerges as a pivotal ally for investigators seeking to unravel illicit crypto transactions. These sophisticated tools harness the power of data visualisation, pattern recognition, and AI-driven analysis to support chain analysis and the various heuristics. Such tools transform the raw data present on blockchains into intelligible insights that aid investigators in identifying patterns, tracing fund flows, and linking wallet addresses to entities. Blockchain analytics tools also facilitate the identification of services that criminals may employ for laundering purposes. In fact, by categorising addresses associated with mixers, fraudulent exchanges, or other laundering mechanisms, these tools enhance investigators’ ability to differentiate between legitimate and illicit transactions.

Below is a list of both free open-source and commercial tools for chain analysis, with a brief description.

Wallet Explorer

URL: https://www.walletexplorer.com/

WalletExplorer is a Bitcoin blockchain explorer, with two additional features: it merges addresses if it thinks that they are part of the same wallet; a wallet can have a name.

Blockchain Explorer

URL: https://www.blockchain.com/explorer

Blockchain Explorer is the most popular and trusted Bitcoin block explorer and crypto transaction search engine.

Blockchair

Blockchair is a blockchain search and analytics engine for Bitcoin, Ethereum, BNB, opBNB, Litecoin, Cardano, Ripple, Polkadot, Dogecoin, Bitcoin Cash, Stellar, Monero, Kusama, eCash, Zcash, Dash, Mixin, Groestlcoin or you can also say it’s an engine that consists of blockchain explorers on steroids. You can filter and sort blocks, transactions, and their content by a variety of different criteria, as well as perform full-text search over the blockchains.

Maltego with Tatum Transforms

Maltego is a comprehensive tool for graphical link analyses that offers real-time data mining and information gathering, as well as the representation of this information on a node-based graph, making patterns and multiple-order connections between said information easily identifiable. Tatum’s integration with Maltego helps investigators traverse the blockchain infrastructure for five blockchains—Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin, Bitcoin Cash, and Dogecoin (limited support) and enables them to discover context and insights on various transactions, all directly within Maltego.

OXT

URL: https://oxt.me/

OXT is a tool designed for exploratory blockchain analysis of the Bitcoin ledger. OXT is the “Other eXploration Tool” and it should become the “Open eXploration Tool” in the future.

Breadcrumbs

URL: https://www.breadcrumbs.app/

Breadcrumbs is a blockchain analytics platform that offers a range of tools for investigating, monitoring, tracking and sharing relevant information on crypto transactions. Inspired by the tale of Hansel and Gretel, the platform is committed to helping user find their way through the blockchain by following the digital breadcrumbs.

Chainalysis

URL: https://www.chainalysis.com/

Chainalysis is more of a traditional blockchain analytics tool that focuses on providing compliance solutions to governments and regulators. It allows you to track transactions, visualise complex data, and perform risk analysis. The main objective behind Chainalysis is to fight crime, bring transparency to the blockchain industry, and build trust. The tool enables governments, businesses, and banks to understand how investors and cypherpunks use cryptocurrency.

CipherTrace

CipherTrace is a crypto intelligence and blockchain analytics tool designed for exchanges, custody providers, governments, regulators, and banks. It provides leading AML compliance solutions to large financial institutions by covering more than 2,000 crypto assets. The tool investigates financial crime, identifies money laundering, monitors risky payments, and tracks travel rule compliance. CipherTrace minimises all risks of criminal activities related to cryptocurrency transfers. It also offers a robust range of blockchain forensic tools that monitor fraud and sanction evasion.

Lost in the Shadows – Demo on a Real-World RaaS Attack

BankCard USA, a Californian electronic payment services provider, recently succumbed to a ransomware attack orchestrated by the Black Basta group. After a month-long negotiation, the company agreed to pay a ransom of $50,000 in bitcoins (considerably lower than the initial demand of $500,000) to prevent the disclosure of sensitive data stolen during a cyberattack in June. The negotiation involved demands for further proof of the data’s authenticity, leading to the ransomware group providing access to a vast trove of files totalling 200 GB. Subsequently, BankCard USA requested the decryption of specific documents, which were provided by Black Basta. The transaction was completed, and Black Basta claimed to have deleted the exfiltrated files. In this demonstration, we try and investigate the flow of the money paid by the firm to the BlackBasta group, by only using free tools - note that the Maltego files are available online.

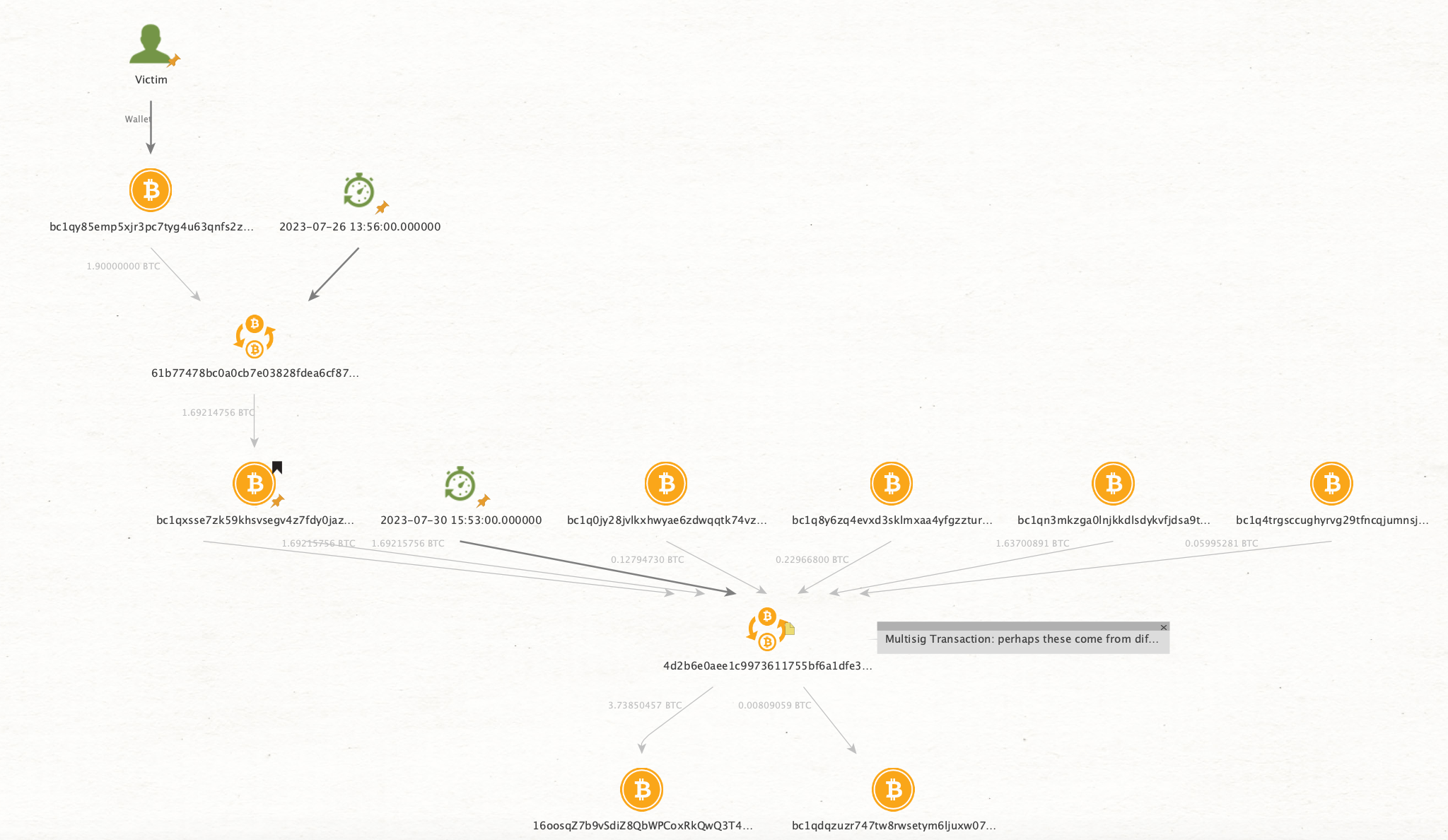

The first challenge involves the retrieval of the wallet address/transactions involved in the payment of the ransom. By means of a cross-analysis, i.e., by looking for transactions of $50,000 in the Bitcoin blockchain on the specific dates reported by the news, we are able to catch the wallet address that received the ransom payment from the transaction involving the transfer of 1.9 BTC:

Addr

bc1qxsse7zk59khsvsegv4z7fdy0jazaex8lqgut3yfx4872f44xxwvsutuv8r

TX

61b77478bc0a0cb7e03828fdea6cf8739ab42845f606c40a175a78a2d2dcbb80

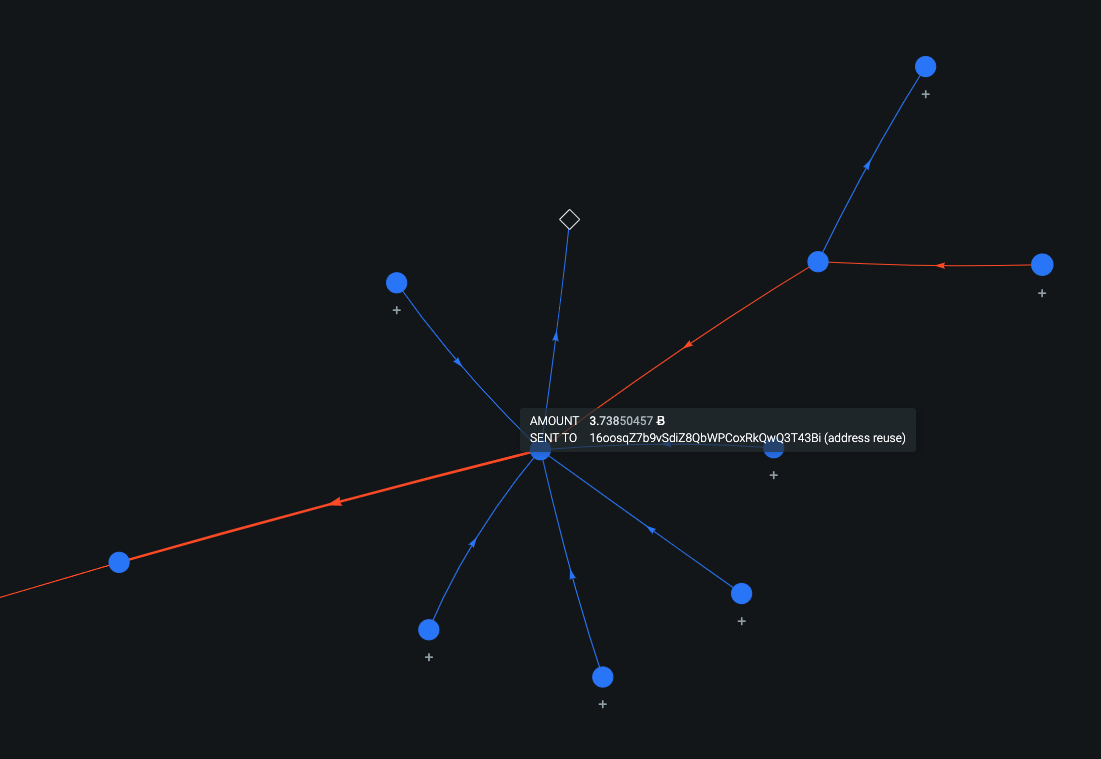

At this point, we can start our follow-the-money analysis using graphical tools like Maltego and/or OXT. Notably, after the first output transaction from the wallet address, we find a transaction that forwards 3.73 BTC.

TX

4d2b6e0aee1c9973611755bf6a1dfe362e882a6f0c5f92d646e6da59e991ace4

We may hypothesise that such an amount was gathered as loot incoming from various attacks, including our 1.9 BTC ransom. This is a clear example of another challenge: during our investigations, we must make hypotheses that will (hopefully) be confirmed or rejected later on.

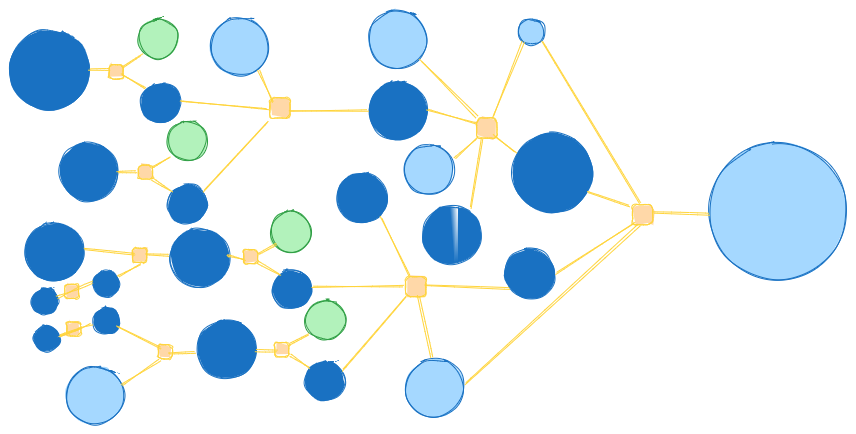

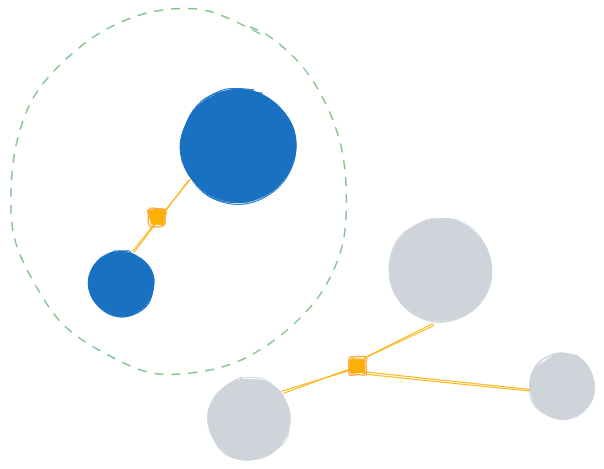

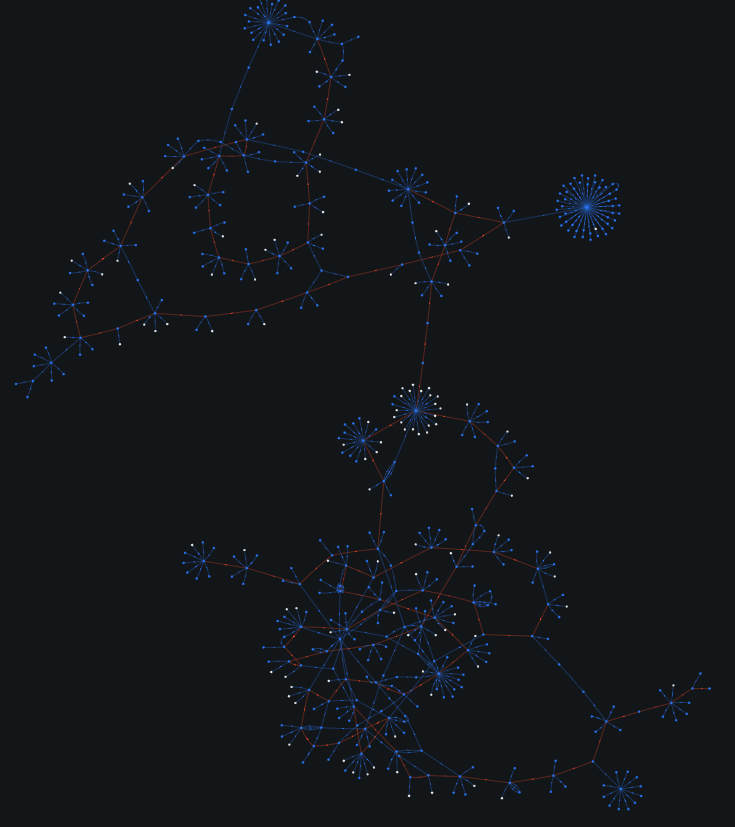

The images below depict the graph of our current analysis, respectively, from Maltego and OXT.

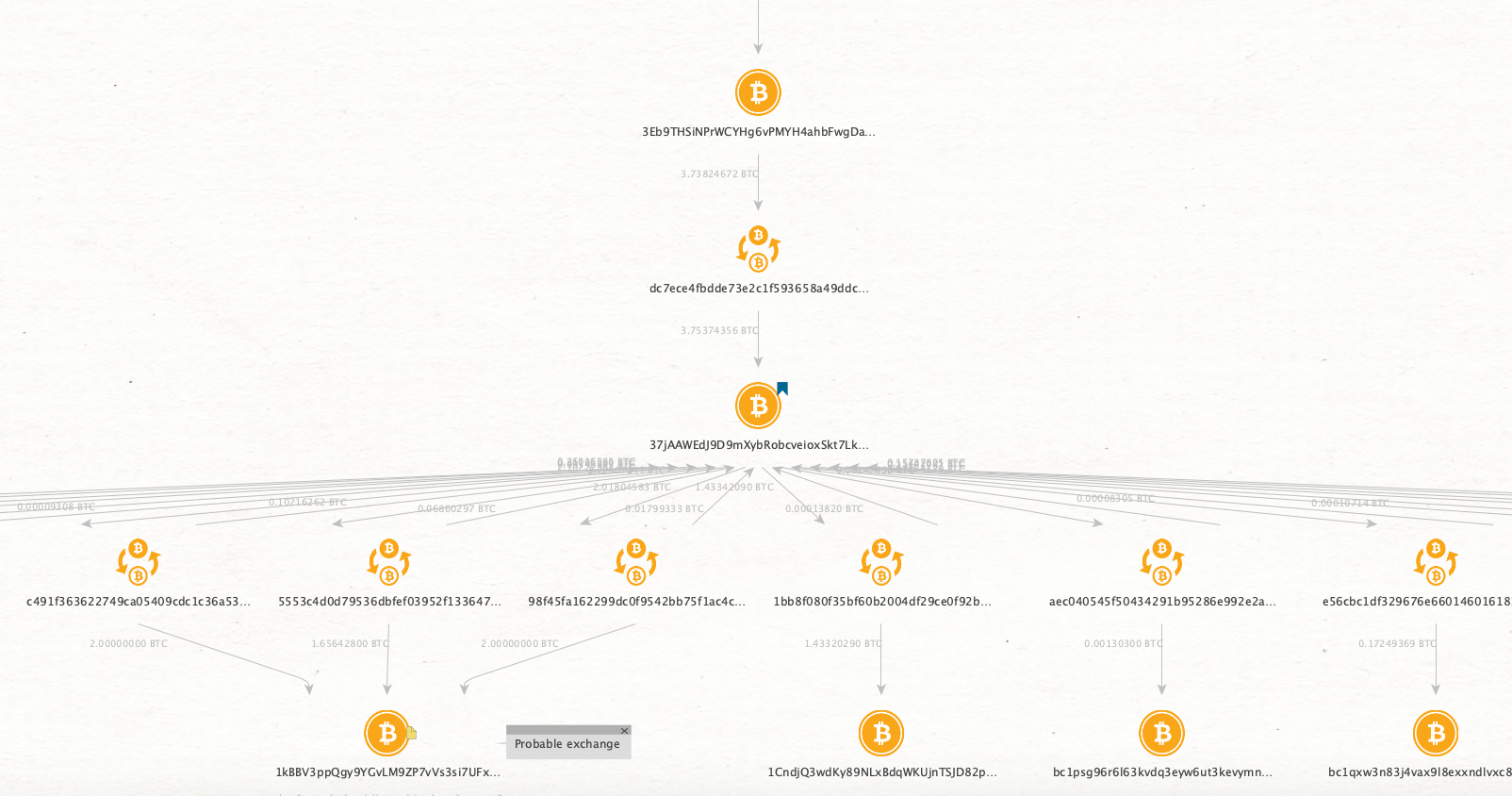

At this point, by further following the output transactions, we unfortunately reach soon a blind alley: the ransom has been immediately moved through a mixing/exchange service named ChangeNow, which in turn has multiple transactions with Binance.

For the sake of demonstration, the image below – note that it is not a constellation! – gives an idea of the exponential number of transaction nodes (each node is a transaction in OXT) that makes it impossible to infer the path taken by the initial amount of money. Sadly, we can already conclude our (unlucky) analysis.

The choice of this specific attack is not fortuitous, as it represents a clear example of how it is difficult to trace cryptocurrencies, especially when we are dealing with organised cybercrime. Nevertheless, by glancing at the latest graph, we can see most of the techniques discussed above (i.e., peel chain, mixers, etc.) in action.

Conclusions

Cryptocurrency Investigation and Forensics stand as pivotal tools in the relentless pursuit of financial transparency and accountability within the realm of cryptocurrencies. These methods and technologies enable investigators to navigate the intricate dance of illicit financial transactions, tracing the flow of dirty money through complex networks, layers of pseudonymity, and obfuscation techniques. This kind of investigations may help to study organised crimes and extrapolate peculiar patterns employed by criminals for the sake of profiling.

However, it is essential to remark that Cryptocurrency Investigation and Forensics, while invaluable, often face formidable challenges. Criminals continuously adapt and employ diverse techniques, as explored in our real-world demonstration earlier in this article. Consequently, a comprehensive strategy that combines state-of-the-art forensic practices with robust regulatory frameworks and international collaboration remains imperative in the ongoing battle against cryptocurrency-related financial crimes. In fact, when criminals successfully convert stolen cryptocurrency assets into fiat currency, cooperation between cryptocurrency exchanges and law enforcement agencies becomes paramount. These partnerships enable authorities to freeze accounts, recover illicitly obtained funds, and, critically, extract vital personal information from exchanges. This information, in turn, assists law enforcement in apprehending wrongdoers, as it enables them to freeze bank accounts, block passports, and track related assets.

Instances of criminals liquidating substantial amounts of Bitcoin following ransomware attacks, cyber fraud, drug trafficking, and illegal weapons trade have become more prevalent in recent years. The surge in anti-money laundering mechanisms can be attributed to the adoption of advanced technologies like big data and artificial intelligence. Traditional AML systems are increasingly inadequate in the face of evolving threats, but these new technologies are aiding AML compliance officers in addressing challenges such as poor implementation, expanding regulation, administrative complexity, and reducing false positives.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Money_laundering

- https://www.investopedia.com/terms/m/moneylaundering.asp

- https://alessa.com/blog/cryptocurrency-money-laundering-aml/

- https://www.fraudinvestigation.net/cryptocurrency/

- https://www.europol.europa.eu/cms/sites/default/files/documents/Europol%20Spotlight%20-%20Cryptocurrencies%20-%20Tracing%20the%20evolution%20of%20criminal%20finances.pdf

- https://www.chainalysis.com/blog/common-blockchain-analysis-mistakes-cryptocurrency-investigations/

- https://www.coindesk.com/learn/how-big-brother-tracks-criminal-crypto-transactions/

- https://originstamp.com/blog/how-to-trace-bitcoin-transactions/

- https://m.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLIBmWVGQhizLrPjpFMN5bQdbOZRxCQXUg

- https://kpmg.com/au/en/home/insights/2021/08/blockchain-analytics-tools-follow-money-in-ransomware-cases.html

You may also enjoy

-

(Gen)AI4CySec

Jul 13, 2024 • 5 min read

-

How to Capture a PCAP for your Hungry Wireshark

Feb 8, 2023 • 3 min read

-

Visual Cryptography Explained

Oct 21, 2022 • 15 min read